Scotland's Craven Civil Service Under the SNP

Magnus Linklater's opinion piece on how craven Scotland's civil service has become under the SNP could not have come at a better time!

The civil servants who authorised public money to be spent on nail varnish, yoga classes and driving lessons ought to be hauled before MSPs to explain their cowardly behaviour.

As should self-aggrandising SNP ministers who think they should be treated 'like royalty' in airports.

Scotland's Craven Civil Service (August 03, 2023)

Magnus Linklater has a real go at what Scotland's once proud, independent civil service has become under the SNP - a tame lapdog instead of a watchdog (see link to The Times below).

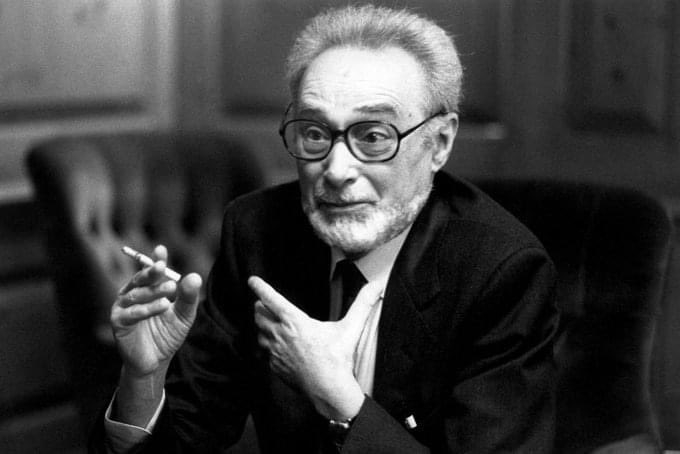

I rather like Primo Levy's scathing dismissal of these Yes Men and Women - "...functionaries ready to believe and to act without asking any questions."

Certainly has the ring of truth when it comes to Scotland's ferries scandal and trans baloney about self-ID, for example!

Civil service must never be the SNP’s lapdog

It’s the duty of Scottish officials to provide good management not promote independence

The nearest I ever got to a genuine Yes Minister moment was when I found myself sitting in on an Arts Council discussion between a Scottish minister and a leading civil servant.

It turned on whether the minister would agree to extra spending. As we walked out I said to the civil servant I was unsure what had been agreed. “Indeed,” he said, “that’s just the way we like it.” It was a reply Sir Humphrey Appleby would have relished: leave it to us, we know what’s best and we will do it on our terms not yours.

Infuriating, inscrutable but absolutely independent — a civil service answerable only to its masters, there to serve the interests of the state.

What happens, however, when the nature of that state is open to question? Or, to put it another way, where do the loyalties of a permanent secretary lie when the masters he serves wish to break up the very state that appointed him?

That is the dilemma facing John-Paul Marks, the permanent secretary in Scotland. On the one hand, his is an appointment agreed by Whitehall which serves the best interests of the United Kingdom. On the other he works for a government pledged to deliver independence and end its relationship with that same UK.

As Marks said when questioned by a Holyrood committee: “We serve the government of the day. That includes with regards to constitutional reform . . . we provide policy advice including the development of [papers] for this government to set out its constitutional objectives.”

So far so reasonable. If, however, those constitutional objectives amount to promoting the interests of the SNP, where is the dividing line between serving the public interest and “party-political cheerleading” — as one critic put it?

Marks would doubtless defend the funds spent on publishing a series of papers setting out the conditions that might apply under independence. But his department seems to have gone further. As The Times reported last week, civil servants have been posting social media messages on government channels highlighting the merits of independence.

One suggested that “independence could renew Scotland’s democracy”. Another said there was evidence that some similarly sized European countries were “more successful than the UK”. This sounds more like propaganda than good management.

Alister Jack, the Scottish secretary, believes a line has been crossed. He has spoken of the “responsibility to spend taxpayers’ money wisely” and questioned whether there is a need for a minister for independence. “It therefore seems clear to me,” he said, “that to use Scottish government funds and civil service resources to design a prospectus for independence, or support a minister. . . is simply irresponsible.”

Even Simon Case, the cabinet secretary who proposed Marks’s appointment, is having doubts. He said it would be “unusual and a bit worrying” if UK civil servants were being used to try to break up the country. He told a Lords committee he was looking at issuing “further clarification and guidance” to Scottish civil servants about “what is and isn’t appropriate spending”.

We will see where that goes but ultimately Marks’s allegiance is to Humza Yousaf, the first minister, and not Whitehall. These days Scottish permanent secretaries may still, in theory, be appointed by the cabinet secretary but in practice the first minister gets the person he or she wants. So Yousaf, unsurprisingly, has come out firmly on the side of Marks. He says the UK government has no right “to curb the work that we are democratically elected to do”.

I guess he has a point. But when a civil service is bent on proselytising for government policies it tends to erode the service’s independence and its overriding duty to represent the interests of the people rather than the political objectives of ministers. Nowhere was that more obvious than when it came to the contract to provide island ferries — one of the greatest stains on the record of the present government.

When ministers decided to award the contract to its favoured company without proper procurement insurance in place, it was the responsibility of civil servants to point out the risk. Whether they did so or not is unrecorded. No evidence has emerged, however, of a written warning — the kind that civil servants place on the record to suggest there might be a breach of the ministerial code.

What this suggests is a civil service that tends to see all decisions through the prism of delivering independence, even when those may come with a risk to public funds.

This is not, of course, the first government to try to bend a civil service to its will. Margaret Thatcher was clear that those who headed the great Whitehall departments on her watch would be assessed on whether they were “one of us” or “not one of us” — and if they failed to sign up for the project, they tended to be sidelined. When in the late 1980s Sir William Reid, a civil servant who had worked with her at the Department of Education, was proposed as permanent secretary at the Scottish Office, she vetoed the appointment and Sir Russell Hillhouse was chosen instead.

The Thatcherite approach was memorably summed up by Sir Richard Mottram, permanent secretary at the Department for Transport, giving evidence to a Commons committee in 2002. He said: “I always compare [the civil service] to a rather stupid dog. It wants to do what its master wants and it wants to be loyal to its master and above all it wants to be loved for doing that.”

This is not a healthy state of affairs. We do not want a lapdog civil service. What we want instead is a watchdog.