Freedom of Speech

As I read this opinion piece by Paul Vallely in The Independent I wondered to myself what the writer's views would have been at the time Monty Python's 'Life of Brian' was released.

Would he have called for the film to be banned?, as some leading Christians did at the time, or would Paul Vallely have defended the right of believers and non-believers alike to criticise organised religion by challenging its dogma and enthusiasm for controlling people's lives.

Curiously as an experienced commentator on religious affairs, Vallely fails to mention the 'fatwa' handed down to Salman Rushdie over his book 'The Satanic Verses' even though this medieval punishment called for every 'good' Muslim to murder Rushdie for his 'blasphemy' in writing about Islam in a critical or challenging way.

The problem, from Vallely's point of view, seems to stem from the lack of self-restraint by critical authors or filmmakers rather than the reaction of people who regard violence or even murder as a legitimate response to words and images with which they disagree.

I've yet to see The Interview, but I suspect the real reason for North Korea's hysterical response is not the cartoon violence in the movie, but the fact that it pokes fun at a sinister, Stalinist figure who is surrounded by a vile personality cult that makes him out to be a living 'God'.

Now which is more offensive: a harmless Hollywood film that satirises a dictator or a political system that enslaves its own people?

The Sony Hack and the ethics of free speech

With freedom of speech comes the responsibility to use it wisely, something the US hasn't shown over Sony

By PAUL VALLELY - The Independent

They dressed as Uncle Sam and arrived decked out in the Stars and Stripes in cinemas all across the United States on Christmas Day for the premiere of the anti-North Korean spoof movie The Interview. One cinema manager introduced the Sony film by reciting "My Country 'Tis of Thee". A coarse comedy – in which a pair of bumbling journalists are recruited by the CIA to assassinate North Korean premiere Kim Jong-un – became an improbable symbol of free speech.

"I'm here to show support for the US," said one university professor. And, added another ticket-buyer, "to show that we don't take any garbage from those guys in North Korea". One cinema manager concluded: "We are taking a stand for American values," and then added, without evident irony, "and hoping to make some money from the movie."

It all seemed a reductio ad absurdum of the high-minded arguments of freedom of expression advanced by Democrats in Hollywood and Republicans in Washington.

In at least one cinema, however, the audience fell silent when the scene arrived in which Kim Jong-un dies as his helicopter is downed and Mr Kim's head explodes. Perhaps for a moment they took on board why the North Koreans have reacted so aggressively, complaining to the United Nations that "such a film on the assassination of an incumbent head of a sovereign state" was tantamount to an "undisguised sponsoring of terrorism".

Defending freedom of speech, Voltaire is frequently summarised as having said: "I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it." In other words, we know whether we really defend free speech only when someone says something with which we seriously disagree.

Freedom of speech is not, of course, absolute. Few would defend the right of a liar to shout "fire" in a crowded cinema, though the ethics might possibly be more problematic if the shouter were a North Korean protester. But even though freedom of expression is essential to the full flow of information needed for a participative democracy to work, we nonetheless place constraints on it.

Free speech is not the right to say whatever you like, about whatever or whomever you like, whenever you like. As a society we routinely restrict freedom of speech to keep the nation safe, maintain public order, ensure individuals have fair trials, preserve copyright or trade secrets, prevent the incitement of racial or religious violence, outlaw degrading pornography and protect children.

And even where speech is unfettered, having the right to say something does not mean it is always wise to do so. Danish newspapers had the right to publish anti-Islamic cartoons of the Prophet Mohamed wearing a bomb in his turban. But the violent reactions from Muslims around the world, in which several people died, suggested that the editor of the paper that did publish might have been better to have exercised the virtue of self-restraint.

It is not to deny the right of free expression to suggest that publishers have responsibilities as well as rights. Google acknowledged that more recently when it pulled an incendiary anti-Islamic video in Egypt and Libya, after the killing of a US ambassador and three other Americans. It might have been useful had it considered the issue before the deaths.

The unfettered exercise of a right can bring unpredicted consequences – as Sony executives learned when the movie corporation's confidential data was released on to the internet and its hard drives wiped.

Yet such is the binary nature of modern American politics that it proved impossible for even a President as subtle and intelligent as Barack Obama to acknowledge even a flicker of this complexity. He could have made points about the distinction between the acts of a US citizen or corporation and those of its government. Instead he blundered in with an undifferentiated declaration, as if free speech were a right which trumped all others. Sony had made a mistake, he declared, and paved the way for censorship by foreign dictators.

The North Korean government in Pyongyang has denied it was behind the attack – which it has nonetheless praised as a "righteous deed". Mr Obama, on the advice of the FBI, does not believe that and responded by saying: "They caused a lot of damage, and we will respond. We will respond proportionally, and we'll respond in a place and time and manner that we choose.

Such a knee-jerk response has not gone down well among other major powers. The Russian foreign minister has described the film as described as "aggressively scandalous" and lamented Mr Obama's "threats to take revenge". And the Chinese, despite their increasing irritation with Kim Jong-un's preposterous and cruel behaviour, have refused to agree to Washington's requests to block North Korean cyber-traffic, which mainly passes through China. One government mouthpiece in Beijing has spoken of America's "senseless cultural arrogance".

It's not hard to see what they mean when you consider Hollywood's highly selective targeting of Russia, Iran, North Korea and Islamists in its limited search for cinematic villains. Hollywood needs to show greater imagination or, as Beijing suggested, better manners.

Good manners may well bear more fruit in international diplomacy than does talk of rights or even responsibilities. Sad, then, that the response of a body in the US which calls itself the Human Rights Foundation is to suggest it will buy copies of the dubious film and drop them from balloons flying over North Korea.

The problem here is not freedom of speech but adolescent arrogance. The United States would do well to ignore North Korea's childish monkey jibe and finally to put an end to its Wild West tendency to shoot its mouth off first and ask questions later.

Paul Vallely is visiting professor in public ethics at the University of Chester

Free speech outcry as images of the Flying Spaghetti Monster are banned from London South Bank University for offending religious people

By JAMIE MERRILL - The Independent

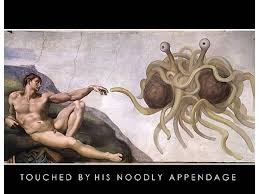

It was meant as a humorous poster to promote a secular society during a university start of term event, but the image of Michelangelo’s famous ‘Creation of Adam’ fresco featuring the satirical deity the Flying Spaghetti Monster has sparked an unlikely freedom of speech row.

The Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster came about as a humorous response to the teaching of intelligent design in American schools in 2005. It has since caught on as an anti-religion statement and become popular with secular societies on British university campuses.

The offending poster was put up at London South Bank University last week by non-religious students from the South Bank Atheist Society, only for it to be reportedly removed by student union officials for being “religiously offensive”.

Initially the secular student society reported it was told that “Adam’s genitals” were the issue before union officials allegedly told them the posters caused “religious offences” and their stall was banned from the start-of-term student event.

The campus row has been seized upon by the British Humanist Association (BHA) and the National Federation of Federation of Atheist, Humanist and Secular Students Societies (AHS) who have condemned the poster’s removal as “utterly ridiculous” and part of “rising tide of frivolous censorship” at British universities.

Choe Ansari, 21, president of the South Bank Atheist Society, which put up the posters, said “This incident is just one of a catalogue of attempts to censor our society. I never expected to face such blatant censorship and fragile sensibilities at university, I thought this would be an institution where I could challenge beliefs and in turn be challenged.”

Ms Ansari, a second-year English student, added that during her time at the university she has seen “religious sensibilities trumping all other rights with no space for argument, challenge or reasoned debate”.

Andrew Copson, BHA chief executive, said “This silliness is unfortunately part of an on-going trend. In the last few years we have seen our affiliated societies in campus after campus subjected to petty censorship in the name of offence – often even when no offence has been caused or taken.

“Hypersensitive union officials are totally needlessly harassing students whose only desire is to get on and run totally legitimate social and political societies.”

Rory Fenton, president of the AHS, added “We are very concerned by the tendency to censor our affiliated societies for fear of offending religious sensitivities by overly zealous union representatives. Universities need again to be reminded to recognise our members’ right to free speech: the same rights that also ensure freedom of expression for religious students, adherents to Flying Spaghetti Monster, whoever they are included. Universities must recognise that their duty is to their students, not their students’ beliefs.’

This pasta-based freedom of speech row comes after the London School of Economics was forced to apologise to two students from a secular and humanist society who were forced to cover up T-shirts featuring pictures from a satirical comic strip Jesus and Mo.

The row over images of the “Jesus & Mohammed” satire itself followed a rising tide of criticism that universities were stifling freedom of speech by allowing gender segregated lectures to be held by Islamic student groups.

Barbara Ahland, the president of London South Bank University’s student union, said: “The Students Union has been made aware of an alleged incident that took place at the Refreshers’ Fayre last week. We are taking the allegation very seriously and an investigation is taking place.”

A spokesperson for the University said it “hosts student societies on campus with a wide range of viewpoints” and works to “achieve an inclusive and supportive environment for all of our students“.

They dressed as Uncle Sam and arrived decked out in the Stars and Stripes in cinemas all across the United States on Christmas Day for the premiere of the anti-North Korean spoof movie The Interview. One cinema manager introduced the Sony film by reciting "My Country 'Tis of Thee". A coarse comedy – in which a pair of bumbling journalists are recruited by the CIA to assassinate North Korean premiere Kim Jong-un – became an improbable symbol of free speech.

"I'm here to show support for the US," said one university professor. And, added another ticket-buyer, "to show that we don't take any garbage from those guys in North Korea". One cinema manager concluded: "We are taking a stand for American values," and then added, without evident irony, "and hoping to make some money from the movie."

It all seemed a reductio ad absurdum of the high-minded arguments of freedom of expression advanced by Democrats in Hollywood and Republicans in Washington.

In at least one cinema, however, the audience fell silent when the scene arrived in which Kim Jong-un dies as his helicopter is downed and Mr Kim's head explodes. Perhaps for a moment they took on board why the North Koreans have reacted so aggressively, complaining to the United Nations that "such a film on the assassination of an incumbent head of a sovereign state" was tantamount to an "undisguised sponsoring of terrorism".

Defending freedom of speech, Voltaire is frequently summarised as having said: "I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it." In other words, we know whether we really defend free speech only when someone says something with which we seriously disagree.

Freedom of speech is not, of course, absolute. Few would defend the right of a liar to shout "fire" in a crowded cinema, though the ethics might possibly be more problematic if the shouter were a North Korean protester. But even though freedom of expression is essential to the full flow of information needed for a participative democracy to work, we nonetheless place constraints on it.

Free speech is not the right to say whatever you like, about whatever or whomever you like, whenever you like. As a society we routinely restrict freedom of speech to keep the nation safe, maintain public order, ensure individuals have fair trials, preserve copyright or trade secrets, prevent the incitement of racial or religious violence, outlaw degrading pornography and protect children.

And even where speech is unfettered, having the right to say something does not mean it is always wise to do so. Danish newspapers had the right to publish anti-Islamic cartoons of the Prophet Mohamed wearing a bomb in his turban. But the violent reactions from Muslims around the world, in which several people died, suggested that the editor of the paper that did publish might have been better to have exercised the virtue of self-restraint.

It is not to deny the right of free expression to suggest that publishers have responsibilities as well as rights. Google acknowledged that more recently when it pulled an incendiary anti-Islamic video in Egypt and Libya, after the killing of a US ambassador and three other Americans. It might have been useful had it considered the issue before the deaths.

The unfettered exercise of a right can bring unpredicted consequences – as Sony executives learned when the movie corporation's confidential data was released on to the internet and its hard drives wiped.

Yet such is the binary nature of modern American politics that it proved impossible for even a President as subtle and intelligent as Barack Obama to acknowledge even a flicker of this complexity. He could have made points about the distinction between the acts of a US citizen or corporation and those of its government. Instead he blundered in with an undifferentiated declaration, as if free speech were a right which trumped all others. Sony had made a mistake, he declared, and paved the way for censorship by foreign dictators.

The North Korean government in Pyongyang has denied it was behind the attack – which it has nonetheless praised as a "righteous deed". Mr Obama, on the advice of the FBI, does not believe that and responded by saying: "They caused a lot of damage, and we will respond. We will respond proportionally, and we'll respond in a place and time and manner that we choose.

Such a knee-jerk response has not gone down well among other major powers. The Russian foreign minister has described the film as described as "aggressively scandalous" and lamented Mr Obama's "threats to take revenge". And the Chinese, despite their increasing irritation with Kim Jong-un's preposterous and cruel behaviour, have refused to agree to Washington's requests to block North Korean cyber-traffic, which mainly passes through China. One government mouthpiece in Beijing has spoken of America's "senseless cultural arrogance".

It's not hard to see what they mean when you consider Hollywood's highly selective targeting of Russia, Iran, North Korea and Islamists in its limited search for cinematic villains. Hollywood needs to show greater imagination or, as Beijing suggested, better manners.

Good manners may well bear more fruit in international diplomacy than does talk of rights or even responsibilities. Sad, then, that the response of a body in the US which calls itself the Human Rights Foundation is to suggest it will buy copies of the dubious film and drop them from balloons flying over North Korea.

The problem here is not freedom of speech but adolescent arrogance. The United States would do well to ignore North Korea's childish monkey jibe and finally to put an end to its Wild West tendency to shoot its mouth off first and ask questions later.

Paul Vallely is visiting professor in public ethics at the University of Chester

Religious Censorship (17 February 2014)

I don't know what's got into students these days - or some of them at least.

I didn't know whether to laugh or cry after reading this report in the Independent about the London South Bank University banning a poster of the Flying Spaghetti Monster.

On a personal level I find lost of things about religion quite offensive, but so long as people don't try to foist their views on me - what other people believe is really none of my business.

If the Students Union follows this logic to its ridiculous conclusion, the should be banning the Film Club from showing Monty Python's 'Life of Brian' or or the university's book shop from selling Salman Rushdie's book, the Satanic Verses.

Free speech outcry as images of the Flying Spaghetti Monster are banned from London South Bank University for offending religious people

It was meant as a humorous poster to promote a secular society during a university start of term event, but the image of Michelangelo’s famous ‘Creation of Adam’ fresco featuring the satirical deity the Flying Spaghetti Monster has sparked an unlikely freedom of speech row.

The Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster came about as a humorous response to the teaching of intelligent design in American schools in 2005. It has since caught on as an anti-religion statement and become popular with secular societies on British university campuses.

The offending poster was put up at London South Bank University last week by non-religious students from the South Bank Atheist Society, only for it to be reportedly removed by student union officials for being “religiously offensive”.

Initially the secular student society reported it was told that “Adam’s genitals” were the issue before union officials allegedly told them the posters caused “religious offences” and their stall was banned from the start-of-term student event.

The campus row has been seized upon by the British Humanist Association (BHA) and the National Federation of Federation of Atheist, Humanist and Secular Students Societies (AHS) who have condemned the poster’s removal as “utterly ridiculous” and part of “rising tide of frivolous censorship” at British universities.

Choe Ansari, 21, president of the South Bank Atheist Society, which put up the posters, said “This incident is just one of a catalogue of attempts to censor our society. I never expected to face such blatant censorship and fragile sensibilities at university, I thought this would be an institution where I could challenge beliefs and in turn be challenged.”

Ms Ansari, a second-year English student, added that during her time at the university she has seen “religious sensibilities trumping all other rights with no space for argument, challenge or reasoned debate”.

Andrew Copson, BHA chief executive, said “This silliness is unfortunately part of an on-going trend. In the last few years we have seen our affiliated societies in campus after campus subjected to petty censorship in the name of offence – often even when no offence has been caused or taken.

“Hypersensitive union officials are totally needlessly harassing students whose only desire is to get on and run totally legitimate social and political societies.”

Rory Fenton, president of the AHS, added “We are very concerned by the tendency to censor our affiliated societies for fear of offending religious sensitivities by overly zealous union representatives. Universities need again to be reminded to recognise our members’ right to free speech: the same rights that also ensure freedom of expression for religious students, adherents to Flying Spaghetti Monster, whoever they are included. Universities must recognise that their duty is to their students, not their students’ beliefs.’

This pasta-based freedom of speech row comes after the London School of Economics was forced to apologise to two students from a secular and humanist society who were forced to cover up T-shirts featuring pictures from a satirical comic strip Jesus and Mo.

The row over images of the “Jesus & Mohammed” satire itself followed a rising tide of criticism that universities were stifling freedom of speech by allowing gender segregated lectures to be held by Islamic student groups.

Barbara Ahland, the president of London South Bank University’s student union, said: “The Students Union has been made aware of an alleged incident that took place at the Refreshers’ Fayre last week. We are taking the allegation very seriously and an investigation is taking place.”

A spokesperson for the University said it “hosts student societies on campus with a wide range of viewpoints” and works to “achieve an inclusive and supportive environment for all of our students“.

Blasphemy! (25 January 2014)

I wonder what punishment local councillors in Newtonabbey would come up with for anyone rash enough to laugh at the 'Life of Brian'- the hilarious Monty Python film?

So, here's a clip from the movie which might give the moral guardians of County Antrim some food for thought.