Ich Bin Ein Berliner

The bad news is that a man claiming to be a refugee, fleeing persecution and violence in Pakistan, seems to be responsible for the murderous Islamist attack on Berlin.

The good news is that another citizen had the presence of mind to follow this coward as he attempted to flee the scene and followed him for two kilometres before alerting the police to his whereabouts.

Who knows at this stage who has been killed and maimed: local Berliners, visitors from other countries, or different parts of Germany, people with a variety of beliefs (other Muslims perhaps) and, of course, those with no religious convictions at all.

Whatever motivation the murderer may claim his actions are bound to be driven by hate of the 'live and let live' attitude which is embodied by Germany, in particular, and western secular countries in general.

I was standing in that exact spot beside Kaiser Willhelm Church exactly two years ago in December 2014 and so I could just as easily have been one of those mown down by a cowardly religious fanatic in a giant truck.

But rather than be cowed by their actions its time to show solidarity with the people of Germany and Berlin - to arouse the spirit of yesteryear in which President John F Kennedy declared "Ich bin ein Berliner".

So I, for one, plan to return to Berlin in 2017.

Article and link to The Atlantic magazine

http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2013/08/the-real-meaning-of-ich-bin-ein-berliner/309500/

The Real Meaning of Ich Bin Ein Berliner

In West Berlin in 1963, President Kennedy delivered his most eloquent speech on the world stage. The director of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum tells the evocative story behind JFK’s words.

Associated Press

Subscribe to The Atlantic’s Politics & Policy Daily, a roundup of ideas and events in American politics.

Other than ask not, they were the most-famous words he ever spoke. They drew the world’s attention to what he considered the hottest spot in the Cold War. Added at the last moment and scribbled in his own hand, they were not, like the oratory in most of his other addresses, chosen by talented speechwriters. And for a man notoriously tongue-tied when it came to foreign languages, the four words weren't even in English.

Ich bin ein Berliner.

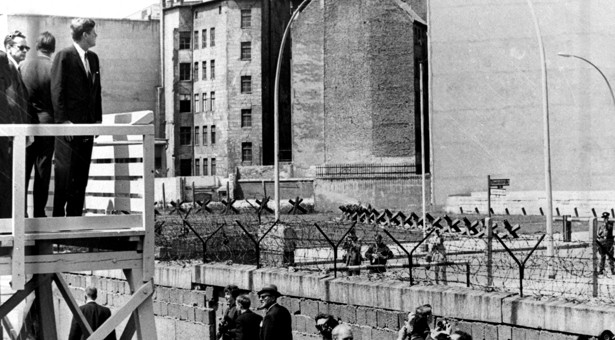

These words, delivered on June 26, 1963, against the geopolitical backdrop of the Berlin Wall, endure because of the pairing of the man and the moment. John F. Kennedy’s defiant defense of democracy and self-government stand out as a high point of his presidency.

To appreciate their impact, one must understand the history. After World WarII, the capital of Hitler’s Third Reich was divided, like Germany itself, between the communist East and the democratic West. The Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev described West Berlin, surrounded on all sides by East Germany, as “a bone in my throat” and vowed to “eradicate this splinter from the heart of Europe.” Kennedy feared that any future European conflict, with the potential for nuclear war, would be sparked by Berlin.

At their summit meeting in Vienna in the spring of 1961, Khrushchev warned Kennedy that he would sign a treaty with East Germany restricting Western access to West Berlin. In response, Kennedy announced a major military buildup. In a television address to the nation on July 25, 1961, he described the embattled city as “the great testing place of Western courage and will” and declared that any attack on West Berlin would be viewed as an attack on the United States.

The speech had its desired effect. Khrushchev backed down from signing the treaty, even as thousands of East Germans continued crossing into West Berlin in search of freedom. In the early morning of August 13, 1961, the East German government, with Soviet support, sought to put this problem to rest, by building a wall of barbed wire across the heart of Berlin.

Tensions had abated slightly by the time Kennedy arrived for a state visit almost two years later. But the wall, an aesthetic and moral monstrosity now made mainly of concrete, remained. Deeply moved by the crowds that had welcomed him in Bonn and Frankfurt, JFK was overwhelmed by the throngs of West Berliners, who put a human face on an issue he had previously seen only in strategic terms. When he viewed the wall itself, and the barrenness of East Berlin on the other side, his expression turned grim.

Kennedy’s speechwriters had worked hard preparing a text for his speech, to be delivered in front of city hall. They sought to express solidarity with West Berlin’s plight without offending the Soviets, but striking that balance proved impossible. JFK was disappointed in the draft he was given. The American commandant in Berlin called the text “terrible,” and the president agreed.

So he fashioned a new speech on his own. Previously, Kennedy had said that in Roman times, no claim was grander than “I am a citizen of Rome.” For his Berlin speech, he had considered using the German equivalent, “I am a Berliner.”

Moments before taking the stage, during a respite in West Berlin Mayor Willy Brandt’s office, JFK jotted down a few words in Latin and—with a translator’s help—the German version, written phonetically: Ish bin ein Bearleener.

Afterward it would be suggested that Kennedy had got the translation wrong—that by using the article ein before the word Berliner, he had mistakenly called himself a jelly doughnut. In fact, Kennedy was correct. To state Ich bin Berlinerwould have suggested being born in Berlin, whereas adding the word ein implied being a Berliner in spirit. His audience understood that he meant to show his solidarity.

Emboldened by the moment and buoyed by the adoring crowd, he delivered one of the most inspiring speeches of his presidency. “Two thousand years ago, the proudest boast was ‘Civis Romanus sum,’ ” he proclaimed. “Today, in the world of freedom, the proudest boast is ‘Ich bin ein Berliner!’ ”

With a masterly cadence, he presented a series of devastating critiques of life under communism:

There are many people in the world who really don’t understand, or say they don’t, what is the great issue between the free world and the communist world. Let them come to Berlin … There are some who say that communism is the wave of the future. Let them come to Berlin … And there are even a few who say that it’s true that communism is an evil system, but it permits us to make economic progress. Lasst sie nach Berlin kommen— let them come to Berlin!

Kennedy cast a spotlight on West Berlin as an outpost of freedom and on the Berlin Wall as the communist world’s mark of evil. “Freedom has many difficulties, and democracy is not perfect,” he stated, “but we have never had to put a wall up to keep our people in.” He confidently predicted that, in time, the wall would fall, Germany would reunite, and democracy would spread throughout Eastern Europe.

The words rang true not only for the hundreds of thousands of people who were there but also for the millions around the world who saw the speech captured on film. Viewing the video today, one still sees a young statesman—in the prime of his life and his presidency—expressing an essential truth that runs throughout human history: the desire for liberty and self-government.

At the climax of his speech, the American leader identified himself with the inhabitants of the besieged city:

Freedom is indivisible, and when one man is enslaved, all are not free. When all are free, then we can look forward to that day when this city will be joined as one and this country and this great continent of Europe in a peaceful and hopeful globe.

His conclusion linked him eternally to his listeners and to their cause: “All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin, and therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words Ich bin ein Berliner.”

Subscribe to The Atlantic’s Politics & Policy Daily, a roundup of ideas and events in American politics.

Other than ask not, they were the most-famous words he ever spoke. They drew the world’s attention to what he considered the hottest spot in the Cold War. Added at the last moment and scribbled in his own hand, they were not, like the oratory in most of his other addresses, chosen by talented speechwriters. And for a man notoriously tongue-tied when it came to foreign languages, the four words weren't even in English.

Ich bin ein Berliner.

These words, delivered on June 26, 1963, against the geopolitical backdrop of the Berlin Wall, endure because of the pairing of the man and the moment. John F. Kennedy’s defiant defense of democracy and self-government stand out as a high point of his presidency.

To appreciate their impact, one must understand the history. After World WarII, the capital of Hitler’s Third Reich was divided, like Germany itself, between the communist East and the democratic West. The Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev described West Berlin, surrounded on all sides by East Germany, as “a bone in my throat” and vowed to “eradicate this splinter from the heart of Europe.” Kennedy feared that any future European conflict, with the potential for nuclear war, would be sparked by Berlin.

At their summit meeting in Vienna in the spring of 1961, Khrushchev warned Kennedy that he would sign a treaty with East Germany restricting Western access to West Berlin. In response, Kennedy announced a major military buildup. In a television address to the nation on July 25, 1961, he described the embattled city as “the great testing place of Western courage and will” and declared that any attack on West Berlin would be viewed as an attack on the United States.

The speech had its desired effect. Khrushchev backed down from signing the treaty, even as thousands of East Germans continued crossing into West Berlin in search of freedom. In the early morning of August 13, 1961, the East German government, with Soviet support, sought to put this problem to rest, by building a wall of barbed wire across the heart of Berlin.

Tensions had abated slightly by the time Kennedy arrived for a state visit almost two years later. But the wall, an aesthetic and moral monstrosity now made mainly of concrete, remained. Deeply moved by the crowds that had welcomed him in Bonn and Frankfurt, JFK was overwhelmed by the throngs of West Berliners, who put a human face on an issue he had previously seen only in strategic terms. When he viewed the wall itself, and the barrenness of East Berlin on the other side, his expression turned grim.

Kennedy’s speechwriters had worked hard preparing a text for his speech, to be delivered in front of city hall. They sought to express solidarity with West Berlin’s plight without offending the Soviets, but striking that balance proved impossible. JFK was disappointed in the draft he was given. The American commandant in Berlin called the text “terrible,” and the president agreed.

So he fashioned a new speech on his own. Previously, Kennedy had said that in Roman times, no claim was grander than “I am a citizen of Rome.” For his Berlin speech, he had considered using the German equivalent, “I am a Berliner.”

Moments before taking the stage, during a respite in West Berlin Mayor Willy Brandt’s office, JFK jotted down a few words in Latin and—with a translator’s help—the German version, written phonetically: Ish bin ein Bearleener.

Afterward it would be suggested that Kennedy had got the translation wrong—that by using the article ein before the word Berliner, he had mistakenly called himself a jelly doughnut. In fact, Kennedy was correct. To state Ich bin Berlinerwould have suggested being born in Berlin, whereas adding the word ein implied being a Berliner in spirit. His audience understood that he meant to show his solidarity.

Emboldened by the moment and buoyed by the adoring crowd, he delivered one of the most inspiring speeches of his presidency. “Two thousand years ago, the proudest boast was ‘Civis Romanus sum,’ ” he proclaimed. “Today, in the world of freedom, the proudest boast is ‘Ich bin ein Berliner!’ ”

With a masterly cadence, he presented a series of devastating critiques of life under communism:

There are many people in the world who really don’t understand, or say they don’t, what is the great issue between the free world and the communist world. Let them come to Berlin … There are some who say that communism is the wave of the future. Let them come to Berlin … And there are even a few who say that it’s true that communism is an evil system, but it permits us to make economic progress. Lasst sie nach Berlin kommen— let them come to Berlin!

Kennedy cast a spotlight on West Berlin as an outpost of freedom and on the Berlin Wall as the communist world’s mark of evil. “Freedom has many difficulties, and democracy is not perfect,” he stated, “but we have never had to put a wall up to keep our people in.” He confidently predicted that, in time, the wall would fall, Germany would reunite, and democracy would spread throughout Eastern Europe.

The words rang true not only for the hundreds of thousands of people who were there but also for the millions around the world who saw the speech captured on film. Viewing the video today, one still sees a young statesman—in the prime of his life and his presidency—expressing an essential truth that runs throughout human history: the desire for liberty and self-government.

At the climax of his speech, the American leader identified himself with the inhabitants of the besieged city:

Freedom is indivisible, and when one man is enslaved, all are not free. When all are free, then we can look forward to that day when this city will be joined as one and this country and this great continent of Europe in a peaceful and hopeful globe.

His conclusion linked him eternally to his listeners and to their cause: “All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin, and therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words Ich bin ein Berliner.”