Trump Sucks Up to Turkey's Erdogan

Can anyone think of a good reason to explain why Donald Trump gave President Erdogan of Turkey the 'green light' to invade Syria and attack the Kurds?Here's video of Trump attending the grand opening of Trump Tower in Turkey. Ivanka even thanked Erdogan on Twitter for this deal.— Robert De Niro (@RobertDeNiroUS) October 9, 2019

Gonna say it loud and clear:

TRUMP IS SELLING OUT KURDISH LIVES FOR A FUCKING HOTEL! pic.twitter.com/bHuCaq2Mo9

Trump the Betrayer (08/10/19)

Mr @realDonaldTrump turns on everybody. Now it’s our allies against the recommendation of our military. The question is who is his master and why?nytimes.com/2019/10/07/us/… via @nytimes

2,973 people are talking about this

The New York Times explains how Donald Trump has betrayed the Kurdish people in a behind the scenes deal with President Erdogan of Turkey.

When I lived and worked in London (in the 1980s) there was a large group of exiled Iraqi Kurds on the political scene, mostly members of the Communist Party, who were a fine bunch of people and completely obsessed, understandably, with the fight to establish an independent Kurdistan.

One of the few good things to emerge from the war in Iraq is the establishment of the Kurdish Autonomous Region (KAR) - not an independent country, but the only part of Iraq that has lived in relative peace and security for the past 10 years, and a degree of religious tolerance which is so obviously missing from the Sunni dominated west and the Shia dominated south east of Iraq.

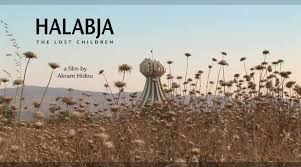

So, I agree completely with this opinion piece by David Aaronovitch because it is without doubt the right thing to do - the Kurds were abandoned after a murderous attack on Halabja by Saddam Hussein whose army used poison gas to kill and maim thousands of Kurdish citizens, including women and children.

The same thing should not be allowed to happen again, in the face of a murderous assault by sectarian religious extremists and if you ask me, this is a valid reason for the west to use air power to defend one of the few examples of a tolerant society that currently exists in the Middle East.

Forget the past. Iraqi Kurds need our help now

The 2003 invasion is irrelevant to what is happening in Mosul now. What matters is preventing the advance of Isis

Late on Tuesday afternoon the phone rang. “You can come on the show”, invited the affable voice, “and tell us whether, in light of the fall of Mosul, you’ve changed your mind about the invasion of Iraq.”

I said no for three reasons. The first was that I knew how the argument must go. The US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 had partly been justified on the grounds that it stopped a jihadi power base developing in the Middle East, but here we are now with the estimated 15,000 men of Isis (the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham) occupying Iraq’s second city.

Isis loosely controls a big stretch of territory in eastern Syria and western Iraq and has captured millions of pounds of cash in Mosul banks and tonnes of Iraqi military equipment donated or sold by the United States. It threatens the existence of a unitary Iraq, the safety of the Kurdish autonomous region and the stability of the whole area.

So wasn’t this all down to the toppling of Saddam Hussein who, bad as he was, had held all this religious extremism in check? Wasn’t this a practical lesson in the folly of intervention?

The incisive John Humphrys, on the BBC Today programme yesterday, put this case as if it was a simple paraphrase of the Universally Agreed Truth. And, I suspect, most people would broadly agree with it. I don’t.

In response I would have pointed out the attractions of my own entrenched position. By the time of the Arab Spring in 2011 the elected Iraqi government, although not composed of regional Abraham Lincolns, seemed to have reached agreement with Sunnis in the west of the country that politics, not violence, was a better way of settling problems. There were lawless places, badly governed towns and cities, and corruption, but with a breathing space and good will Iraq itself was a going entity.

Although the high-handedness of Nouri al-Maliki, the Iraqi prime minister, towards representatives of the Sunni minority has been disastrous, what actually led to the Isis catastrophe was the chaos and war in Syria.

The inability of the Syrian opposition to take on an Assad regime armed with helicopters, planes and heavy artillery led to an attritional war in which extreme elements became more powerful as time went by.

During this time, western policy was not characterised by intervention. Far from it. As in 1991, at the end of the first Gulf war, the West offered rhetorical encouragement to the enemies of the dictator, but no practical help. Into the resulting void stepped the jihadis — determined, courageous, supplemented by foreign fighters and supplied by people in the Gulf. All of this was predictable and all of it was predicted.

And in any case (I might throw in, just for jollies) how do you know how the 77-year-old Saddam, or his succeeding sons, would have handled the fall-out from Syria if his regime was still in place, as it probably would have been?

This argument leads us nowhere. We did invade Iraq and — much more recently — we didn’t intervene by taking out Assad’s air force in Syria. Whichever trench you want to occupy, sticking in it and lobbing verbal shells at the other side seems self-indulgent to me.

My second reason for declining to shoot my mouth off on late night telly was straightforward lack of expertise. And not just mine. I do my best to follow developments in Iraq and Syria as reported by brave journalists on the spot or as analysed by regional specialists, but it is practically impossible to get a good idea of what goes on in areas “controlled” by groups such as Isis.

Do they have the capacity actually to run — as opposed to terrorise — a city the size of Birmingham? What are the logistics of taking on the core of the Iraqi armed forces as they approach Baghdad?

Fifteen thousand fighters is a small basis from which to challenge a state, otherwise Isis might be in Damascus now, and remarkably little has been seen so far of the Iraqi air force.

Is the objective just to control a strategic slice of territory from which to launch terrorist attacks on anyone Isis doesn’t like? Or is it a fully fledged pre-2001 Afghan-style theocracy? And whose objective, exactly, are we talking about (how does a group like Isis make decisions anyhow)? I don’t know and I’m not picking up many convincing answers.

And third, given the above, I’m confused about what can be done about it. I mean, what realistically can be done about it, within the limitations of public opinion?

The nations of the “West” (by which I mean the liberal democracies) discuss defence in a peculiar way, as if the world had not changed in 30 years.

We quibble about the role of Nato and decide our defence budgets and force capabilities with minimal reference to each other. When the National Audit Office laid into the government over the reduction of the size of the Army yesterday, you would have thought that the rest of the world had simply vanished. It was just about us.

In fact most of our strategic interests are held in common and we — all of us — have some very big stakes in what is happening right now around Mosul. And it should be possible to work out together where we draw our lines in the sand.

The US State Department has already committed to “a strong, co-ordinated response to push back against this aggression”, which I imagine may mean helping, with the use of air power, to prevent further Isis movement. If so, a quid pro quo must be a renewed attempt at cross-sectarian peace-making.

Last week in the Kurdish Autonomous Region of Iraq (KAR), peaceful for nearly a decade, relatively prosperous and relatively democratic, there was a report of protests by some villagers against Exxon Mobil exploration — peaceful protest, aimed at elected officials. The KAR and its 4.8 million inhabitants represent the one incontrovertible gain of the last Iraq war. We must do everything short of putting boots on the ground to help the Kurds to defend themselves against Isis and similar groups.

Britain and France should give President Obama whatever encouragement he needs to take this action, and render whatever assistance the Americans might require.

We don’t have to agree on anything else — 2003, WMD, Syrian red lines, whatever — just this.

Defend the Kurds (143/06/14)

When I lived and worked in London (in the 1980s) there was a large group of exiled Iraqi Kurds on the political scene, mostly members of the Communist Party, who were a fine bunch of people and completely obsessed, understandably, with the fight to establish an independent Kurdistan.

One of the few good things to emerge from the war in Iraq is the establishment of the Kurdish Autonomous Region (KAR) - not an independent country, but the only part of Iraq that has lived in relative peace and security for the past 10 years, and a degree of religious tolerance which is so obviously missing from the Sunni dominated west and the Shia dominated south east of Iraq.

So, I agree completely with this opinion piece by David Aaronovitch because it is without doubt the right thing to do - the Kurds were abandoned after a murderous attack on Halabja by Saddam Hussein whose army used poison gas to kill and maim thousands of Kurdish citizens, including women and children.

The same thing should not be allowed to happen again, in the face of a murderous assault by sectarian religious extremists and if you ask me, this is a valid reason for the west to use air power to defend one of the few examples of a tolerant society that currently exists in the Middle East.

Forget the past. Iraqi Kurds need our help now

By David Aaronovitch - The Times

The 2003 invasion is irrelevant to what is happening in Mosul now. What matters is preventing the advance of Isis

Late on Tuesday afternoon the phone rang. “You can come on the show”, invited the affable voice, “and tell us whether, in light of the fall of Mosul, you’ve changed your mind about the invasion of Iraq.”

I said no for three reasons. The first was that I knew how the argument must go. The US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 had partly been justified on the grounds that it stopped a jihadi power base developing in the Middle East, but here we are now with the estimated 15,000 men of Isis (the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham) occupying Iraq’s second city.

Isis loosely controls a big stretch of territory in eastern Syria and western Iraq and has captured millions of pounds of cash in Mosul banks and tonnes of Iraqi military equipment donated or sold by the United States. It threatens the existence of a unitary Iraq, the safety of the Kurdish autonomous region and the stability of the whole area.

So wasn’t this all down to the toppling of Saddam Hussein who, bad as he was, had held all this religious extremism in check? Wasn’t this a practical lesson in the folly of intervention?

The incisive John Humphrys, on the BBC Today programme yesterday, put this case as if it was a simple paraphrase of the Universally Agreed Truth. And, I suspect, most people would broadly agree with it. I don’t.

In response I would have pointed out the attractions of my own entrenched position. By the time of the Arab Spring in 2011 the elected Iraqi government, although not composed of regional Abraham Lincolns, seemed to have reached agreement with Sunnis in the west of the country that politics, not violence, was a better way of settling problems. There were lawless places, badly governed towns and cities, and corruption, but with a breathing space and good will Iraq itself was a going entity.

Although the high-handedness of Nouri al-Maliki, the Iraqi prime minister, towards representatives of the Sunni minority has been disastrous, what actually led to the Isis catastrophe was the chaos and war in Syria.

The inability of the Syrian opposition to take on an Assad regime armed with helicopters, planes and heavy artillery led to an attritional war in which extreme elements became more powerful as time went by.

During this time, western policy was not characterised by intervention. Far from it. As in 1991, at the end of the first Gulf war, the West offered rhetorical encouragement to the enemies of the dictator, but no practical help. Into the resulting void stepped the jihadis — determined, courageous, supplemented by foreign fighters and supplied by people in the Gulf. All of this was predictable and all of it was predicted.

And in any case (I might throw in, just for jollies) how do you know how the 77-year-old Saddam, or his succeeding sons, would have handled the fall-out from Syria if his regime was still in place, as it probably would have been?

This argument leads us nowhere. We did invade Iraq and — much more recently — we didn’t intervene by taking out Assad’s air force in Syria. Whichever trench you want to occupy, sticking in it and lobbing verbal shells at the other side seems self-indulgent to me.

My second reason for declining to shoot my mouth off on late night telly was straightforward lack of expertise. And not just mine. I do my best to follow developments in Iraq and Syria as reported by brave journalists on the spot or as analysed by regional specialists, but it is practically impossible to get a good idea of what goes on in areas “controlled” by groups such as Isis.

Do they have the capacity actually to run — as opposed to terrorise — a city the size of Birmingham? What are the logistics of taking on the core of the Iraqi armed forces as they approach Baghdad?

Fifteen thousand fighters is a small basis from which to challenge a state, otherwise Isis might be in Damascus now, and remarkably little has been seen so far of the Iraqi air force.

Is the objective just to control a strategic slice of territory from which to launch terrorist attacks on anyone Isis doesn’t like? Or is it a fully fledged pre-2001 Afghan-style theocracy? And whose objective, exactly, are we talking about (how does a group like Isis make decisions anyhow)? I don’t know and I’m not picking up many convincing answers.

And third, given the above, I’m confused about what can be done about it. I mean, what realistically can be done about it, within the limitations of public opinion?

The nations of the “West” (by which I mean the liberal democracies) discuss defence in a peculiar way, as if the world had not changed in 30 years.

We quibble about the role of Nato and decide our defence budgets and force capabilities with minimal reference to each other. When the National Audit Office laid into the government over the reduction of the size of the Army yesterday, you would have thought that the rest of the world had simply vanished. It was just about us.

In fact most of our strategic interests are held in common and we — all of us — have some very big stakes in what is happening right now around Mosul. And it should be possible to work out together where we draw our lines in the sand.

The US State Department has already committed to “a strong, co-ordinated response to push back against this aggression”, which I imagine may mean helping, with the use of air power, to prevent further Isis movement. If so, a quid pro quo must be a renewed attempt at cross-sectarian peace-making.

Last week in the Kurdish Autonomous Region of Iraq (KAR), peaceful for nearly a decade, relatively prosperous and relatively democratic, there was a report of protests by some villagers against Exxon Mobil exploration — peaceful protest, aimed at elected officials. The KAR and its 4.8 million inhabitants represent the one incontrovertible gain of the last Iraq war. We must do everything short of putting boots on the ground to help the Kurds to defend themselves against Isis and similar groups.

Britain and France should give President Obama whatever encouragement he needs to take this action, and render whatever assistance the Americans might require.

We don’t have to agree on anything else — 2003, WMD, Syrian red lines, whatever — just this.